Despite my disability, and to a certain extent because of it, Kim and I remain social animals. We love spending time with friends, in our home or occasionally out on the town. I’m sure I’m not the only wheelchair user who feels this way. However, due to our accessibility challenges and other health problems, socializing… Continue reading 10 Tips for How to Socialize with a Wheelchair User

Tag: General Musings

Appearances

(Photo credit: Wikipedia) Wheelchairs are scary. How do I know this? The mothers tell me. They tell me by the way that they pull their children close when they see me coming. Okay, maybe that’s a bit melodramatic. These mothers may be, after all, protecting me from their snotty nosed little brats. Or they may… Continue reading Appearances

The MS Goldilocks Zone

The Earth resides in a Goldilocks zone – the temperature is just right. If our orbit was any further from the sun then all water on the planet would be in the form of ice, and life probably couldn’t exist. If our orbit was any closer to the sun then any water would be in… Continue reading The MS Goldilocks Zone

How Far I Have Fallen

(Photo credit: Wikipedia) One day last week during a transfer from the toilet seat to my wheelchair, I felt my body suddenly pitch forward, and I knew I was fucked. It had been a couple of years since I had fallen. Back when I was a semi-walker, cane user, or scooter rider, I would fall… Continue reading How Far I Have Fallen

Musings of a Distractible Mind

That’s the name of a blog I just found, thanks to my friend Alice. Dr. Rob Lambert, a primary care physician and the author of Musings of a Distractible Mind, lends us his unique perspective. In most doctor-patient relationships, there exists an invisible wall. Although we generally admire our physicians, we often find them aloof,… Continue reading Musings of a Distractible Mind

Disability Retirement- A Broken System

(Photo credit: Wikipedia) I don’t even know if disability retirement is the correct term, but that’s how I usually describe the fact that I no longer work. Actually, today is the four-year anniversary of my last day at the office. I believe this milestone gives me the right and perhaps the obligation to stand on… Continue reading Disability Retirement- A Broken System

A Farewell Mother’s Day Present

The photo to the left is from Mother’s Day, 1972. I’m the pink shirt guy. My mother passed away in the autumn of 2008, so it’s been five years since our last Mother’s Day together. I’d like to share with you the video gift I gave her that year. It’s hard to know what to… Continue reading A Farewell Mother’s Day Present

The Importance of Being Aimless

It’s not as if I’m a prisoner all winter. Even in the cold months I manage to leave the house often, either in my minivan or by negotiating the neighborhood snowbanks in my wheelchair. But travel becomes purely utilitarian. It’s about getting from point A to point B in the least painful way. Today, I… Continue reading The Importance of Being Aimless

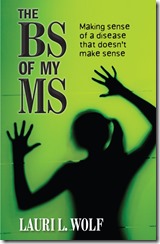

Book Recommendation – “The BS Of My MS” by Lauri Wolf

A couple of weeks ago I received an email from Lauri Wolf, whom I had never corresponded with before. She indicated that she had been reading my blog, and proceeded to quote me from a February post where I lamented the lack of attention given to PPMS in the literature. “…there’s very little in print… Continue reading Book Recommendation – “The BS Of My MS” by Lauri Wolf

Thought control of robotic arms using the BrainGate system…

Life with paralysis is going to be better in the not so distant future. Thanks Stu for sharing this story. Click below. ** Stu’s Views & M.S. News **: Thought control of robotic arms using the BrainGat…: